Reviews by Massimo Ricci

The A23H chronicle

20180824

ALFRED 23 HARTH / JOHN BELL – Campanula

The second recorded collaboration between Alfred 23 Harth and New Zealand’s John Bell – a conscious multi-purpose percussionist and bower of various sorts of object – materializes three years after 2015’s Camellia, released by Bill Shute’s Kendra Steiner (go for it, too). Besides having originated the track titles, the very Mr. Shute offers an active contribution to this enthralling melange of creative spurts, his deadpan voice reciting snippets of the open-field poems for which he is justly renowned. All of this lodged in a rather lavish package comprising a substantial booklet – “Cooperation” – gathering the visual and textual fruits of the trio’s combined actions from 2013 to 2017.

If this was not enough for the imperishable collecting specimens, there are still 55 minutes of unpigeonholeable acoustics for you to wonder about first, and cherish later. By now the experts (including the latecomers) have memorized the rule: when Harth is involved, discard what’s incontrovertible in the name of a biotic (im)materiality as vivid sonic emanations detail what an insensible simpleton would call a “dream”. Or a nightmare, perhaps, for those whose conception of polyphony is necessarily connected to a resolution. There’s no resolution in this ceaseless search for inevitably ephemeral answers; unable to grasp the latter, we somehow feel indebted to the partakers for letting us at least keep the intuition.

Harth and Bell have been developing a strong bond over the last period, and it shows. The duo appears as a sole entity, merging several issues related to the emission of a tone and the possibilities of manipulation of its conformation and shape. In terms of overall sonority, the strident/charming divergence becomes a logical solution whenever one lends an attentive ear to what’s born within a given mix. The same happens with the juxtapositions of quasi-singable melodies by Harth’s reeds and glowing chords from Bell’s vibes carried on across environments of studio-produced noise (notable example, “Art-illery Breakfast”).

However, never the brain is afforded to settle on an actual context. “Abstraction” is the password, and “no genre” the reply to the password recovery question; the textural gravity and dynamic balance shift systematically, and you just have to follow that whimsical stream. Many times one feels caught in a psychedelic ritual without a direct association of the body; Shute’s poetry fits perfectly at the right junctures, his delivery guiding the listener during the awakening phases of an improving, if somewhat destabilizing experience. It must be noted that Harth and Bell use their voice as well; this writer particularly appreciates “Worried Men & Wooden Soldiers”, where Mr.23 wheezes something like “I know” (corrections welcome) in a milieu of electronic disfigurements and sombre metallic pulses.

Campanula is an exemplification of the infeasibility of an accurate report when – to paraphrase Shute’s description of Harth’s approach – far-sighted artists open the doors separating diverse types of expression, and walk to the other side. There’s much more than meets the auricular membranes when it comes to a work like this, a means of connection with states of the (non) being that, one way or another, express our deepest humanity. That which may be replete with curiosities, fears and beliefs but (barring the trademark cosmic unintelligence of selected “raconteurs of the unknown”) is ultimately defined by the acceptance of an inescapable fallibility.

By Massimo Ricci in Touching Extremes

20170504

HARTH / SEIDEL / SPERA / VAN DEN PLAS – Malcha

Subsequent to many years spent with Alfred 23 Harth’s output, I find myself in the same position of the proverbial aging individual who learns to manage and optimize the residual energies as opposed to wasting them in a pathetic illusion of “understanding”. There is no actual need of contextualizing, intellectualizing and filing away a microcosm which translates – in sounds – several of the recondite non-meanings comprised by the phases of beingness that do not foresee a so-called “active role”. We acquire what we can, in the meantime developing skills that belong to the unconscious level. They are, in a way, mechanisms of defense against the unknown. It falls on our personal abilities and strengths to absorb the theoretically incomprehensible nuances of that “unknown” to render them a functional component of the most valuable of gifts, intuition.

So we ground a suppositional “knowledge” on a few random elements underlying the conception of this record, another dumbfounding gathering of altered states, wide-eyed dreams and Pollock-esque splashes. For starters, Harth does not “improvise” with the other musicians, as read elsewhere. In this circumstance he should be credited as composer, given that he assembled and organized contributions singly furnished by Wolfgang Seidel, Fabrizio Spera and Nicole Van Den Plas (although, somewhere in there, snippets do appear from a live set played in 2015 by the trio of Harth, Seidel and Spera). The title refers to both a Korean tea, and an ancient Indian legend; the overall sense of this co-action is rooted in the possibility of keeping an artistic flow ongoing through extended temporal spans and geographic distances. In fact, Seidel and Harth have been collaborating, on and off, since 1983; Van Den Plas was once the latter’s spouse, and also one of his very first creative partners; Spera, hailing from Rome, is a frequent associate of the German over the last decade. Quite a variance of human sources and experiences.

Thus, an awful lot for the mind to receive in such a diversity of signals and gestures. This is a veritable decomposable quilt, multitudes of precisely combined small parts attributing momentum to an integrity that exists, breathes – sometimes hard, sometimes more calmly – and (especially) suggests. Initially, Van Den Plas’ puzzling vocalizations seem to predominate in the mix; however, as one keeps learning the contents (be warned: dozens of listens are demanded to do this) the impression of an “abandon hope ye who enter here” sort of premise materializes. The disruptions emerge from the hidden corners: weak sun rays may attempt to break into a shadowy scene – rarefied piano notes, an electric guitar drone, ductile string lines, soft rolling on toms, the unpredictable argot of Harth’s reeds – but they’re only guide lights across a gasping organism desperately seeking for alternative ways to explicit its acoustic spirit.

The electronic/studio treatments considerably increase the music’s fertility, furnishing a damp cellar of undefined reverberations to a tightly configured guild of like-minded explorers. Field recordings are intelligently exercised, ultimately becoming a crucial shade of this uniquely patterned fabric. All in all, Malcha is a somewhat uncomfortable request to deliver ourselves from private expectations: inside its complexity, “horribly crippled” and “flawlessly designed” presume an equal significance. If you feel fit after reading all of the above, then the process of self-disappearance amidst atypical sonorities to blank out the mind’s twisted geometries can officially begin.

Massimo Ricci in Touching Extremes

20150824

ALFRED 23 HARTH/WOLFGANG SEIDEL – Five Eyes

on Moloko+ (Plus 078)

The physiognomy of Five Eyes is as heterogeneous as the fusion of an inauspicious incubus with the realization of being on the path towards a metropolitan enlightenment of sorts. Its acoustic properties contain numberless problems, rigorously to be solved by the listener: doubt must reside in our brain. This record encapsulates uncomfortable truths, surreptitious patterns and surprisingly poetic openings. Each of the eight tracks presents a story that unfolds remorselessly and, at times, awkwardly, leaving no hope for a quiet settlement between Harth and Seidel’s difficult issues and the necessity of a “common” order of things. But an order is present, despite the apparent decompounding of the sonic tissue in various areas. There are threads to follow, and solid rhythms to believe in; never mind what instrument generates what. Perhaps the disc’s most important feature is the “misc” attributed to the couple besides the other sources; that “misc” acts as the fixative that holds everything in place in this implausible fresco. Traits of different species appear to distort the perception of the circumstantial reality. The voices of Nicole Van Den Plas, Bill Shute and Boris Stout allure, affirm and confuse through various episodes, Harth himself pulling a great trick in the final segment “Man-On-The-Side”, typified by his absurdly warped crooning. In “Co-traveler”, what might resemble a multilayered senselessness to the inexpert addressee betrays instead the tortuousness of a wisdom grounded on thousands of undocumented experiences. Caustic frequencies burn; misshapen echoes scare. The perdurability of a given sequence – or, if you will, chordal aura – is in general quite brief. A light flashes, the head is turned to that point; someone whispers and wails, the attention instantly goes there. Finding a method across a wasteland of dramatic urgency is not entirely painless: this is no “laissez-faire” cheapness, there’s nobody around rejoicing for having managed to find textural meaning in a creaking chair in the name of post-Cagean silliness. Still, a measure of relief is gained when “Anticrisis Girl” attempts to caress our previously surcharged auricular membranes: its steady pulse, with a gorgeous loop of tarnished steel string guitar to begin with, carries nevertheless the weight of real significance. But that trip, too, is replete with shifts of atmosphere and unsteady nonchalance: the assonance with the silent internal turbulence defining every sensible person nowadays is almost miraculous. And the pseudo drum ‘n’ bass beat underlining the chaotic multitude of stratifications at the end is a touch of near-perfection. Harth and Seidel go back a long way; their reciprocal knowledge emerges very clearly from this incredible ant nest of lucidly unconventional hypotheses. Referring to the process of re-contextualization of earlier snippets utilized here by the duo, and to the wish of avoiding constrictions of any kind in the assemblage of the work, the drummer calls this music “Herrschaftsfreie” (*), more or less translatable with “without any domination”. I’m not sure that there are so many poseurs – sorry, “artists” – worthy of using the same description today.

(*) The word was originally used in a flyer about Just Music, one of the very first projects by Alfred Harth.

Massimo Ricci in Touching Extremes

20140201

As Yves Drew A Line.Estate

Re Records Hong Kong

Alfred 23 Harth: all instruments & recordings, with brief ghost apparitions by Fabrizio Spera (drums), Luca Venitucci (piano), Choi Sun Bae (trumpet)

Earthly life is mostly shaped by irritating human excrescences and lumps of illusory “happiness” amidst heterogeneous nightmares and extremely welcome, if impermanent segments of calmness. Its components are usually too many to be systematically organized, and – given that brains are not reliable – an excess of messages transmitted in quick batches can cause serious problems. This has always been the principal reason for the idiotic refusal of unidentifiable music: take out of the equation the safety net of a familiar scheme, the firm clutch to a category, the mandatory call to “belonging” to some movement, and the best you can get is a reaction along the lines of “nice, but give me something more accessible”. Evolution slapped in the face, flea-bitten posturing and derelict coolness replacing the tendency to multiple storage and parallel thinking that one could ideally reach via an earnest transonic education.

During my first approach to As Yves Drew A Line. Estate there were surrounding circumstances that transformed the experience in a surreal trip, your reviewer oscillating between a somewhat alert REM state and a whirlwind of different images rapidly materializing and immediately disappearing. However, each subsequent spin brought an unequivocal response: this CD must be ranked among Alfred 23 Harth’s most accomplished opuses as far as “getting to the point” is concerned in his polymorphic vision of all things sound. We might describe it as an electroacoustic documentary synthesizing the bulk of his receptive artistic being. These 21 tracks – few of them are (meaningful) mere snippets – may appear to the musically preliterate as a mishmash manufactured in the name of an anarchy that recognizes its own existence exclusively, but doesn’t attempt to substantiate its contents to render the world a better place. Follow this advice, folks: “Listen. Learn” (…yes, I’m replicating the album’s titling style – all the chapters, minus the third, contain a dot in the names).

Non-convergent conjectures and fast actions find implausible spots to melt as consuming throbs of regurgitated momentariness (“Cityone. Shanti”). Mesmerizing repetitions of tiny incidents extinguish the mind’s will to stray around, furnishing it with coordinates for the retrieval of an analytical geometry. Unshapely reeds seem to lampoon the holy attitude of certain “researchers” interested in reaching the largest quantity of fundings through grimacing and fake sufferance, their asses kept warm by wealthy foundations or steady stipends by well acquainted “cultural” entities. Genuine ascensions (…and no, John Coltrane has nothing to do with this) get scarred by acerbic slices containing ephemeral voices, sloping chorales of uncertain identity, trans-gendered prayers. Breath, sax tones, electronics and unconventional utilization of looping and pitch shifting hammer our capacity of decoding an acoustic message into a flexible sculpture of adaptation to the improbable (“Top Floor Icosahedron. Open Delay”). Backward vocals, distant rain, abrupt surges of discombobulating counter-harmonies, see-sawing minimalism comprising glissando guitars. Everything incisively tailored in the exact instant of the creative spurt, later assembled in Harth’s studio as the ideal depiction of a complexity that only silence can embrace to its full extent. In this case, though, silence is just what we need after taking in the type of multitudinous correspondence of events that, once understood, separates those who live from those who are enslaved by living.

In Touching Extremes

20130613

SAMM BENNETT / ALFRED 23 HARTH / CARL STONE / KAZUHISA UCHIHASHI – The Expats

Kendra Steiner Editions

Alfred 23 Harth: reeds, kaoss pad, dojirak, samples, voice; Carl Stone: computer, Max/MSP, voice, samples; Kazuhisa Uchihashi: electric guitar, daxophone; Samm Bennett: diddley bow, mouth bow, voice, gadgets The highest value of this live set from 2010 in Tokyo derives from the feel of collective connection that it transmits. Purposeful sonic motility born from different experiences and backgrounds, materially explicated by each artist’s insightful levelheadedness. A 160-copy limited edition is the tangible evidence of a special night lighted up by a supergroup of sorts. “Unboxing” starts with a rather imperturbable mood spotted by undecomposable shapes – petite noises, clean-cut guitar and sax notes, well-distributed percussive touches – leading the listener step by step towards a perception-deceiving sphere where the aggregation of antithetical dynamics and tensions flourishes into a beautifully morphing varicolored lattice, a general awareness of inherent fluidity defining the whole track even when sourer samples attempt to prevail in the mix. We could call this a somewhat melodic expansion of collateral fluxes of consciousness. “Eschew Obfuscation, Espouse Elucidation” comprises several degrees of incandescent noise-making; the utilization of more complex deformations of the original sources encompasses clearly visible bodily aspects. There is less room for relief in this potential chaos, but what ultimately wins – here like everywhere else – is a sense of organization holding all the components nicely pasted together, including the seemingly illogical ones. In that regard, the positioning of uncrystallized vocalizations, burbling entities, groaning impressions and scratchy rhythms in parallel with the episodic “aligned” phrase or semi-twisted arpeggio works wonders in generating psychedelic scents of the finest brand. “It’s Also The Things We Choose Not To Put In” is initiated by an implausible “gamelan-in-a-music-box-meets-Jon Hassell” mishmash, from the insides of which additional shots of perspicuous lunacy come forth to uproot the audience. The “acoustic soul” seems to dominate at one point, yet there is enough content of electronic instability; a timbral malleability characterized by aesthetic permeableness (now and then with pseudo-minimalist condiments) is the core of the matter in this circumstance. Actually, the main trait of this quartet corresponds to their ability of rendering unlikely ideas “interiorly toothsome”, stimulating our private focus and adapting capabilities without the need of overwhelming (although a section starting around the eight minute, defined by what sounds as a cross of misshapen ringing alarms and oriental martial art ceremonials would surely be sufficient for many people to get brain-sick). “Alien” – a word this writer is growingly becoming fond of these days, for various reasons – coincides with the occult (in a way) side of the foursome’s action. Deprived of any sign of over-indulgence, this piece’s textural essence transports a willing participant inside the realm of genuine sensual disengagement, not necessarily warranting a quietening welcome to heavenly composure. On the contrary, some of the frequencies can enhance a given state of mind – say, dejection or worrisomeness – up to points of displacement that hyper-sensitive individuals may find hard to be in, if caught in a “down” moment. As always with musicians at this level, being pushed right in front of what the self understands as unendurable is the method for receiving otherwise unachievable explanations.

In Touching Extremes

Alfred 23 Harth: reeds, kaoss pad, dojirak, samples, voice; Carl Stone: computer, Max/MSP, voice, samples; Kazuhisa Uchihashi: electric guitar, daxophone; Samm Bennett: diddley bow, mouth bow, voice, gadgets The highest value of this live set from 2010 in Tokyo derives from the feel of collective connection that it transmits. Purposeful sonic motility born from different experiences and backgrounds, materially explicated by each artist’s insightful levelheadedness. A 160-copy limited edition is the tangible evidence of a special night lighted up by a supergroup of sorts. “Unboxing” starts with a rather imperturbable mood spotted by undecomposable shapes – petite noises, clean-cut guitar and sax notes, well-distributed percussive touches – leading the listener step by step towards a perception-deceiving sphere where the aggregation of antithetical dynamics and tensions flourishes into a beautifully morphing varicolored lattice, a general awareness of inherent fluidity defining the whole track even when sourer samples attempt to prevail in the mix. We could call this a somewhat melodic expansion of collateral fluxes of consciousness. “Eschew Obfuscation, Espouse Elucidation” comprises several degrees of incandescent noise-making; the utilization of more complex deformations of the original sources encompasses clearly visible bodily aspects. There is less room for relief in this potential chaos, but what ultimately wins – here like everywhere else – is a sense of organization holding all the components nicely pasted together, including the seemingly illogical ones. In that regard, the positioning of uncrystallized vocalizations, burbling entities, groaning impressions and scratchy rhythms in parallel with the episodic “aligned” phrase or semi-twisted arpeggio works wonders in generating psychedelic scents of the finest brand. “It’s Also The Things We Choose Not To Put In” is initiated by an implausible “gamelan-in-a-music-box-meets-Jon Hassell” mishmash, from the insides of which additional shots of perspicuous lunacy come forth to uproot the audience. The “acoustic soul” seems to dominate at one point, yet there is enough content of electronic instability; a timbral malleability characterized by aesthetic permeableness (now and then with pseudo-minimalist condiments) is the core of the matter in this circumstance. Actually, the main trait of this quartet corresponds to their ability of rendering unlikely ideas “interiorly toothsome”, stimulating our private focus and adapting capabilities without the need of overwhelming (although a section starting around the eight minute, defined by what sounds as a cross of misshapen ringing alarms and oriental martial art ceremonials would surely be sufficient for many people to get brain-sick). “Alien” – a word this writer is growingly becoming fond of these days, for various reasons – coincides with the occult (in a way) side of the foursome’s action. Deprived of any sign of over-indulgence, this piece’s textural essence transports a willing participant inside the realm of genuine sensual disengagement, not necessarily warranting a quietening welcome to heavenly composure. On the contrary, some of the frequencies can enhance a given state of mind – say, dejection or worrisomeness – up to points of displacement that hyper-sensitive individuals may find hard to be in, if caught in a “down” moment. As always with musicians at this level, being pushed right in front of what the self understands as unendurable is the method for receiving otherwise unachievable explanations.

In Touching Extremes

20130226

DEAD COUNTRY featuring ALFRED 23 HARTH – Gestalt Et Death

on Al Maslakh

Alfred 23 Harth: alto sax, clarinet, vocal, electronics; Şevket Akinci: electric guitar; Umut Çağlar: electric guitar, monophonic synth, tape delay; Murat Çopur: electric bass; Kerem Öktem: drums, percussion

Rip-roaring chronicles from Alfred 23 Harth’s 2011 visit in Turkey, where a partnership – make that “collusion” – was born after the Frankfurter was invited to act there with this local group (previously hidden to this reviewer’s cognition). Gestalt Et Death sounds pretty coarse in terms of recording quality – one would think to a precise artistic preference, sort of a “let’s combine ingredients in the alembic and see what happens”. The force deriving from the interfusion hits right on the chin, the recordings – uneasy to ingest on the introductory attempts in spite of Dead Country’s sparse usage of rock-ish constitutions – possessing the staying power and the emblematic qualities of albums that do not need technical attires and fatuous facades to invite the listener, warranting significant substance instead.

“Horseman’s Most Expensive Effect” is a rather enigmatic “ritual” opening delimited by a hefty vamp: overdriven bass and overwhelming percussiveness, Harth blowing upon them in peculiarly strained fashion. “Fiery Red DC” offers a withering representation of punk jazz, sharp-cornered riffage and muscular drumming the basis for A23H and Çağlar swapping heavy leather before the matter gets mangled into tiny bits of rust-brown dissonance. “96205 Ararat” is the most non-concrete piece on offer, a challenging synth solo spiraling erratically inside a perpetually mutating tapis of percussion and electronics until everything calms down spellbindingly. More gargantuan pseudo-rock structures are found in “Lady Deathstrike’s Healing Factor”, perhaps the track where Harth expresses his on-the-spot creativity at best, alternating trademark sax furore and funnily enlivening “commands” yelled into a microphone and resonating with echo; the finale, a blasting mix of indocile guitars and synthetic misbehavior, is also remarkable.

The longest improvisation is (splendidly) titled “Cessily In Liquid Form Blindly Teleports The Entire Team Rag”; here, methinks, lies the finest moment of the disc, subsequent to an initial robotic oratory: a handsome arabesque depicted by the German on the bass clarinet, layered over a growingly engrossing fixed-tone drone and a clean first, knifelike later axe underlying the function’s exhilarating prospect. The concise “Mr. Burroughs’ Finger” returns to the anarchy of a free-for-all blowout bathed in scathing electricity and odd metered arousal, whereas the conclusive “Jump Off The Timestream” takes shape from deformed/flanging throat emissions and electronics enhanced by ferociously abstract strings, sealing the whole with the type of who-cares-about-defence fusillade that might annihilate your cerebral activity for a while; Harth’s sporadic declamation adds the necessary dose of enigma in a cataclysmal crescendo ended by himself with a terrific wordless invocation.

Serious mayhem overall; play loud. And dig this “vocally improved” version of Mr. 23′s impromptu cogitations: a new color in an already awesome palette. Kudos to Al Maslakh for having had the balls of publishing this stuff, definitely not easy to advertise or squeeze into the average consumer’s will of trying uncomfortable music.

20120523

ALFRED HARTH / CARL STONE – Gift Fig

on Kendra Steiner Editions

A meeting between two big names whose partnership would have been nearly unthinkable just a few years ago. But there’s something that links Alfred Harth with Carl Stone besides their indubitable artistry: the influence of Asian cultures on their respective lives and crafts (one is based in South Korea, the other in Japan). These six tracks constitute a compendium of two concerts occurred in 2009 and 2010 in Frankfurt and Tokyo, but the extremely high quality of the sound and the lack of audience noise makes the CD comparable to a studio work.

The set is basically built upon Stone’s transformation (via Max/MSP) of Harth’s emissions, with subsequent additions of further pre-existing materials. The palette is obviously homogeneous: Harth also treats his “babies” (which include Eastern wind instruments like taepyeongso and dojirak) with a Kaoss pad, and uses bows on the instrument’s bell and in other parts too. Both employ samples and voice. But the description of the sources doesn’t excessively help clarifying how this uncompromising record sounds. The material, at least from what I gathered by repeated listens, appears mostly improvised. Many different scenes succeed in ever-radical spurts, without concessions to any kind of easiness or relief; a latent tension informs the bulk of the sonic settings, which in some moments approach a near-explosive configuration. Percussive aspects are frequently privileged, the mechanical features of the reeds amplified and expanded to become an out-and-out menace: imagine a giant crab walking towards you with bad intentions (“Adler_Kino 23 Gu II”). Somewhere, Harth’s pulmonary exhalations morph into powerful winds deprived of a chunk of the frequency spectrum. And I could go on.

In a way, there’s a “savage ritual” aspect to the whole. Squealing pitches and calmer floating mix, often in the ambit of a single section, with exceptional results. Not a minute passes before some sort of surprise materializes: sampled talkers telling incomprehensible things for us poor westerners, looping junctions attacking the brain from all sides. In the lengthy final track “Adler_Kino 1166-1215 IV” the progressive accumulation of acoustic substances produces such a level of eventful saturation that one foresees fire from the amplifier; maintaining a mental balance in there is not for everybody.

Ultimately, this is a seriously dissonant album that will represent a veritable nightmare if foolishly played as a background for conversation: it will grab you by the ears and destroy your social pleasures. Tough and totally unwilling to open autonomously; treat it like a shut oyster and use the knife of your concentration, provided that the edge is sharp. The pearls inside are several, but they’re not suitable for a glamorous necklace. 133 copies only – you’ve been warned.

20120101

ALFRED 23 HARTH / SOO-JUNG KAE / CHANG U CHOI - Red Canopy

The late Frank Zappa was among the first composers that I know to apply the process of “xenochrony” to music: that is to say, juxtaposing recordings from antithetic settings and diverse eras in a single, studio-generated opus. Red Canopy is founded on a kindred philosophy: the sounds were pre-recorded by each performer in 2005, and four years later Alfred Harth pasted them at Laubhuette in Seoul to produce just over 17 minutes of glorious work, definitely belonging to the schismatic German’s finest.

The tracks are evidently constructed on fleeting intuitions, but every instant counts. It all begins with a duet involving Choi’s double bass and Kae’s piano, the musicians left alone for the necessary time to thrust the listener right into a mood incorporating both thoughtfulness and sense of anticipation. When Harth enters the scene, the initial quietude is cracked by the impulse of telling many things promptly and eloquently. Yet it is in the following sections that we really need to come to terms with the idea that the artists never played unitedly. A track like “Samsa” features the same spirit of a well-adjusted room meeting, the magnificent flotsam and jetsam of a latent interaction consummately collected in what might resemble a chamber arrangement.

The skilful exercising of loops and electronics expands and compounds the primary timbres, setting the instrumental attributes on a boundary line between baffling lyricality and overt experimentation. The 3-inch CD (which comes in a narrow 123-copy printing) ends with the umpteenth question mark, leaving us at a loss – once more – in front of a form of creativity that doesn’t demand continuance or, worse, a format in order to explicit its whole potential.

in Touching Extremes

20110803

7K OAKS - Entelechy

The music on Entelechy was recorded in 2008 at the Open Circuit-Interact Festival in Hasselt, Belgium. That it remained unreleased for three years, regardless of its vibrant energy and out-and-out extraordinariness, tells a lot about what the masses seem to prefer and/or demand in the view of a contemporary label. Better late than never, the CD has finally been issued and those who manage to grab it are going to be delighted. The lineup of 7k Oaks is exactly the same of the first, and equally special debut album: Alfred 23 Harth (tenor sax, bass clarinet, pocket trumpet and electronics), Luca Venitucci (keyboards), Massimo Pupillo (bass) and Fabrizio Spera (drums).

“Seon Avalanche” starts the group’s powerful engine with an assault that might cause someone to secretly wonder “who needs Last Exit?”. A seriously charged “welcome-to-hell” improvisation where communal guts are exalted despite the possibility of watching the single elements at work, as in a continuous shift between a collective camera shot and a series of close ups. Harth manages to extract bits of minimal melody and the occasional howl from the tenor, fusing those visions with the incinerating crunch generated by Pupillo’s viciously overdriven bass and Spera’s now-funky-now-rambling percussive virulence. Venitucci makes himself noticed via irregular stabs of organ-ic dissonance and abrupt intrusions of ungracious arpeggios.

Harth’s trumpet is a galvanizing listen whenever he utilizes it during the performance. However, it is the clarinet that defines – in a somewhat chimpanzee-like attempt of communicating primary impulses – the beginning of “Soziale Plastik”, a piece defined by a looping electronic figure upon which Pupillo’s string and pick-up tampering and Spera’s rubbing and bowing of his set construct a whole castle of uncertainty. Silence almost falls at one point, yet we’re as distant from Wandelweiser modishness as a prosperous porn star is from the hundreds of bulimic models seen walking expressionlessly in Dolce & Gabbana’s parades of human poultry.

“Labor Anti-Brouillard” begins with an electro-trance substratum, soon accompanied by a rather absurd Latin drum pattern which, incredibly, is perfectly functional for the scope. Buzz, hum and iridescent pulse maintain a firm clutch, Harth’s reticent muttering and hiss-and-kiss activities interspersed with droplets of shining light by Venitucci, whose electric timbre is also peculiar and totally effective in its naked minimalism at that precise juncture. The growth in the tension level is palpable: fixed pitches increasing suspense, Pupillo’s macho-ism moving things quite a bit in the low frequency region. However – contrarily to what one could have expected – the quartet does not push the listener back to the initial mayhem, preferring instead to baptize a new version of Chic (and Cassiber)’s classic “At Last I’m Free”, introduced by the most contemplative, quasi-EAI solo by A23H that I’ve heard in a while. Spera , Pupillo and Venitucci flow in with a mix of dissonant piano, metallic harmonics and all-inclusive rumble, turning the atmosphere into avant-noir at the flick of a switch. It remains sort of suspended – the final surge notwithstanding – and leaves us wanting more, a trait which is typical of great records and bands. Both Entelechy and 7k Oaks are unquestionably definable as such, and we need additional recordings of the latter’s blazing interplay to get excited with. Possibly without waiting for so long.

in Touching Extremes

20110427

micro_saxo_phone. edition III

The over 74 minutes of extracurricular activities contained herein – deserving a set of top-class headphones for best results – promise headaches for those who want to keep fantasizing on their favourite things. Ever since the initial “Chukyo” (dedicated to the Japanese university that invited the protagonist to give lectures in 2010) one realizes that Harth observes another kind of reality – or several of them – through a mere reed instrument. Chunks of guitar are employed to add to a small flotilla of kaleidoscopic tricks and treats, percussively resonant traits revealing a weird influence on the brain, left paralyzed at first and completely vacant later on. The way in which the guy totally ignores the rules of good behaviour when subjecting the fruits of his improvisations to the computer is admirable for the absolute lack of prescribed definition and consequent stylistic stringency. And yet, every snippet possesses at least a modicum of sense, the sum of the parts giving birth to uncompromisingly personal statements that transcend probability and worn-out beliefs. Just listen to the magmatic delirium of “Resveratrol”, sort of a gamelan orchestra ending is existence via the crushing wheels of a giant mechanism.

Does anyone know what Gagok is? Neither did I before reading the liner notes. It’s a typical Korean “fake classical music”, with opera singers and all the rest, that Harth masterfully inserted in a great text/sound piece called “Doublespeak”, something that lovers of composers such as Åke Hodell might cherish. The taped voices (which include a fake interview with art photographer Nobuyoshi Araki where both the participants are impersonated by Harth) and the disfigured scenarios defining this nightmare for retarded martyrs are, on the contrary, pure joy for the cognoscenti. Infected and sullied by the hiss of old tapes and reinforced by the shifting howls of a soprano who never in her life could have imagined of getting abused like that, these sounds open the mind better than the whole history of Timothy Leary’s acid tests. And you’ll be able to tie your shoes after the experience.

As soon as a new record by the Seoul resident appears, this narrator starts shivering in fear of the inability of finding a method to illustrate the ingenious excellence of the work. When so much meat is being cooked at once, the task becomes really arduous. But – as always – a pair of receptive ears linked to a head delivered from conventions will help receiving this plethora of altered codes with some grounding. Even if someone mistakes the four episodes of “Surplussed” – electronically treated static masses of alto saxophones – for reversed outtakes recorded on a sun-struck Agfa cassette by a rehabilitated ex-nihilist postindustrial nonentity, or thinks that “Twonky” was performed by a drunk Tibetan monk, we’re sure that the sturdy hands of the little big man are not going to sock the unfortunates that hard.

In Touching Extremes

20100902

ALFRED 23 HARTH - @ Blankies End

Described by its inventor as “another kind of looking back into the last decade”, @ Blankies End is one of the best records that Alfred 23 Harth has released in that period. By analyzing the titles, a forward counting towards 2012 can be detected while observing the recent past. In classically puzzling style, and open to any interpretation by the reader, Harth writes that “…being conscious about every moment we count & live in linearity (…) means a moment within a future moment (2012 is here & now & yesterday)”. The album’s content is both arcane and stimulating; repeated scrutiny is a must. “Ten Tin” contains materials that seem to mix human snoring, chanting monks and bubbling hisses in a conduit, the pace defined by a sort of electrostatic rhythm upon which the clarinet sings with unusual peacefulness, if just temporarily. It’s an inexplicably meditative vision, sounding a little scary at the same time, the grunting tone of Harth’s voice disloyal to the mental image I treasure of him as a timidly smiling gentleman. “Elf” (“eleven”) utilizes distortion in large doses, mashing and mangling snippets of concrete and instrumental substance in homage to the blasphemy of extreme dissonance. The toothsomely vicious results are to be savoured in the restaurant where the finest electroacoustic recipes are served. “Gesternmorgen” is an abstraction: an amassment of simple melodies clashing in adjacency, hyper-acrid reed perspirations, corrosion of heterogeneously alien harmonies and a pinch of disaffection for the cruel world of ordinary music. At the very beginning, “Popol Vuh” might evoke Jon Hassell (the pulse, the nearly tribal atmosphere). The differences become obvious when Harth starts superimposing the different reeds; meanwhile, the background gradually transforms the better intentions in an intimidating mutation of a religious chant, halfway through a sacrificial invocation and the complete disconnection from corporeality. The whole unfolds across undecipherable utterances and other assorted subliminal persuasions. “Twentyhundredtwelve” (namely 2012 or 20+1+2, as the composer would have it) features Choi Sun Bae’s trumpet in a ominous hint to the “enigmatic” year which will define once and for all if those famous prophecies are legitimate or not (curiously, December 21 – the presumed ending date – is also Frank Zappa’s birthday). Again, the voice is a fundamental ingredient of the track, which grows on the listener memorably amidst drones, squeals, gurgles, vociferous solos and warped lamentations, a remarkable episode in Harth’s recorded output. “Back Lantern” explores the fringes of the frequency region with a quick wink to the sweet cheapness of certain synthetic patches from two decades earlier (more on that later); nonetheless, the underlying extraterrestrial mantras and ebbing-and-flowing glottolalia are what actually corresponds to its actual muscle, highlighting a type of spiritual quest that sees the fear of the unknown as a regular incidence in an advanced being’s daily reflection. If someone had taught me to pray like this as a young child, I’d still be there at the church. “Der Schlaf Ist Eine Süsse Melodie” ends the set in typical A23H fashion, and I’m not going to reveal the secret. Go to the artist’s website and ask for a copy of this CDR pronto.

In Temporary Fault

20100830

ALFRED 23 HARTH - @ eighties end

On a first listen, the connection between the above milestone and @ Eighties End doesn’t appear so easy (nothing is when this artist is involved). For starters, both recordings were realized at the closing stages of a decade (2009 the former, 1989 this). Then, a somewhat melancholic clarinet characterizes big chunks of the music(s) quite profoundly. Yet the reason behind Harth’s choice of retrieving this work from the archives is the perception of a reborn interest for some of the sounds in vogue in the 80s, with particular reference to notable presets (which, sure enough, this record comprises). The collection includes segments from a pair of diverse soundtracks: Antigone, a theatre piece played at Düsseldorf’s Schauspielhaus of which Mr. 23 was the musical director at the time, and Lachen, Weinen, Lieben, a film then broadcasted by ZDF. If the theatre act calls for something dramatically relating performers and listeners – for example, “Antigone.Nacht” offers exactly that in a progression of atmospheres at times reminiscent of Thierry Zaboitzeff – the soundtrack for the television feature shows a new facet of this multi-talented man, who manages to achieve credibility in that difficult field despite the intermittent use of timbres that everybody knows inside and out

(…mainly from Korg workstations: lots of musicians, including yours truly, fell prey of those pads in that epoch) but, in his hands, are meshed and delivered with such subtleness that they often result as adequate, even to this day. The beauty of a sound always depends on the context and, especially, on the person who exploits it. In that sense, Harth is invulnerable: the control on the mechanisms and the correct sequencing of the sonic occurrences remains inflexible, the concepts are expressed without excess of discursiveness (which would contradict the music’s designed role in this circumstance). Ultimately, this

is a slight detour from the renowned capriciousness of the German’s acoustic craft that permits a partial relief interspersed with a modicum of weirdness (as it happens in “Antigone.Ölfässer”, the general sonority enhanced by the actors via enormous oil cans in a peculiar Mad Max-like scenario).

In Temporary Fault

20100701

ALFRED HARTH – Brocken/Biest 01/01

In 2001, Alfred Harth was enduring a bit of physical trouble, related to the many years spent with a piece of reed around his neck. He decided at that time to give an unusual spin to his music by starting to use electronics quite frequently while diminishing the use of the heavy honker.

The first result of this switch is the live composition "Brocken/Biest 01/01", a 72-minute trip through hundreds of garbled shards mostly informed by a tendency to technological riffraff and schismatic sampladelia. The title is an evident pun on “broken beat”, but in German it translates as “lump (piece) of beast” (!), whereas 01/01 – recalling the binary code – is actually a mere reference to the recording date (January 2001). Divided in 13 segments consecutively linked (as in a perfect 12-inch mix - in fact, one of the effects used is that of the cyclical crunch of vinyl), this is an exciting aspect of Harth’s crafty engineering skills. However, it is not something to assimilate painlessly; the quantity of events utilized by the Frankfurter is huge, the brain struggling to collocate each detail in the correct place with just a transitory listen (which, incidentally, should not be done with ANY record). Suffice to say that there are traces of unimaginable obsessions everywhere, fused in an individual concoction of misshapen visions and bizarre backgrounds that sound intimidating, paradoxical, or both; the whole sustained by rhythms that can be either spastic or disco-regular. Myriads of samples are seamed in masterful fashion, their consecutiveness generating a “let’s-see-what-comes-now” kind of expectation in the listener. Incomprehensible radio snippets, the Warner Bros audio logo camouflaged in liquid equalization, surrealistically twisted power chords, voices from inconceivable places (with particular relevance to intriguing Oriental accents that, pertinently deformed by AH, give the idea of a continuous gurgle generated by someone who’s about to throw up. Difficult to explain in words, but fantastic in terms of pulse). A few tracks even show a peculiar, definitely unintentional resemblance to chosen chapters of Muslimgauze’s discography. The best method for being invaded and ultimately conquered by this great mishmash – to be especially treasured by those who appreciated the “Mother Of Pearl” series – is keeping it going ad infinitum for at least four or five hours, letting it become a part of your physicality while completely intoxicating the senses. You’ll soon realize that reality does not look the same from which things had started, and it feels damn good.

in TEMPORARY FAULT

20100629

ALFRED 23 HARTH – Laub

Laub is an only apparently simpler specimen of Harthian creativity, yet it’s without a doubt the more enigmatic item of this pair (and, in truth, among the most cryptic offerings I’ve heard from the Seoul expatriate). The record’s name means “foliage”, a word also referenced in AH’s private studio “Laubhuette”, which stands for “hut made of leaves”. The music – mainly obtained by alternating indefinable stringed instruments, electronic/concrete materials and echoes of Korean activity – is essentially a cycle of “remixes, fragments and field recordings” captured between 2004 and 2006 and comprising rare gems such as the impenetrable “Nonunhappiness”, an exhilarating – and unfortunately short - remix of a snippet of “Domestic Stories” (somehow evoking Elliott Sharp’s cybernetic guerrillas), and assorted chunks of “iGnorance”, Harth’s homage to composer Yun I-sang, of whom the protagonist uses a beautiful string section from a work called Piri , re-baptized “Piri II” for the occasion. There’s a perceptible severance between the nude acoustic soul of a crude improvisation like “Peripathy, A Sufi Prayer In Corea” and the acousmatic complexity of “Spagat”, an impressive cross of theatric vocals (by Yi Soonjoo, Alfred’s life partner) and whimpering dogs recorded in a farm. “Direct Jazz II” utilizes superimposed sax flurries upon a multitude of strata including synthetic improbability, shortwaves and metropolitan moods. The mind-boggling “Rueckbrick” closes the CD on a slightly anguishing note caused by fickle electro-multiplicity (picture a stoned Jon Hassell/Terry Riley Siamese couple) and various species of mystifying glissando. Overall, the album’s singular components - whose blending may initially appear ludicrous - coalesce consistently after the third or fourth dutiful scrutiny, confirming the man’s ability in pulverizing the original meanings of his objects of study and combining them into artistic reports that, once brought to light, instantly overshadow the globally accepted standardization of composers appositely deified by the regime universally identified as “specialized press”.

in TEMPORARY FAULT

20100331

This Earth! (ECM 1264)

In 1983, ECM’s honcho Manfred Eicher “nominated” Alfred Harth as the musical director of This Earth!, with the chance of choosing the participants to the ensuing recording. The lineup is astrophysical: Maggie Nicols, Paul Bley, Barre Phillips and Trilok Gurtu assist the record’s nominal proprietor along nine chapters entirely composed by him. The target was, in the principal’s words, “to contribute to help rising the ecological consciousness at that time, and point out the preciousness of the planet we are living on. Three years later Tchernobyl happened and set a new sign within the ecological movement..”

Lots of literary foundations and personal discoveries are infused in this creation, officially released in 1984. Sri Aurobindo, Alan Watts’ The Wisdom Of Insecurity, Abraham Maslow (already quoted in the past in a Goebbels & Harth track, “Life Can Be A Gestalt In Time”). And then, Fritz Perls, Stanislav Grof, John C. Lilly’s studies on dolphin communication, Ken Wilber, Michael Murphy. Harth was, and still is, deeply interested and moved by the exploration of the “extraordinary human potentials”; to this day, he declares himself a follower of Transhumanism.

Accordingly, a number of selections amount to a direct allusion to the improvement of the individual. “Relation To Light, Colour And Feeling” begins with a poised yet intense dialogue between Bley and Phillips to open up in spacious linearity, splendidly rendered in unison by Nicols and Harth, Gurtu adding a few percussive flavours when Nicols starts vocalizing more abstractly. “Body And Mentation” is one of the most lyrical episodes of an uncharacteristically “tranquil” record as opposed to the Frankfurter’s standards, a beautiful counterpoint branded by the inner confidence of musicians who know how to move in and around a composition even when blindfolded. The chief’s tenor leads the dance with a poignant invocation, and nothing needs to be said anymore when that heartfelt call gives room to a sizeable measure of stirring passion. “Energy: Blood/Air” is a moderately swinging piece whose melodic jitteriness approaches post-bop territories - chiefly articulated by Nicols’ scatting - and another curious setting for the notions of Harth, who accompanies the English singer with a tone that could easily be defined as classic. A concise assertion by Bley is delivered in straightforward fashion, Phillips closing the segment with a solo of his own.

Gurtu opens “Come Oekotopia” with suggestive echoes, then a sax/bass duet enters the picture in somewhat edgy conversation. Again, it’s the main actor who steals the show with a trademark dramatic departure before the English vocalist joins in. The opening of “Waves Of Being” might be compared to certain pages from Lindsay Cooper’s book, a smart chapter of modern-day chamber flair instantly pushed towards liberal swing by Bley and Phillips, who exchange ideas and energies like two well informed friends. The succeeding passages - arcoed strings and bass clarinet proceeding jointly, holding hands in stunning beauty - are an authentication of the kind of artistic brilliance able to reallocate a tune from “normal” to “attractive” with a simple idea. The final “Transformate, Transcend Tones And Images” is sung by Nicols over an arco bass/piano rarefaction, evoking shades of Julie Tippetts ancestry. An appropriate winding up for a program that never really exalts or excites, but keeps us with the mind positively firm and the ears constantly vigilant, catching small signs and slight changes that nevertheless weigh a lot in the sonic economy.

This is an effort that discards histrionically charged gestures, revealing a different side of Harth. This man’s presence on ECM has been infrequent to say the least but – in the moments in which it occurred – some outstanding concepts surfaced in unpredicted ways, unquestionably distant from the lows to which the label has recurrently crumbled down from the almost unreachable benchmarks of its glorious times. Not a surprise that we’re still waiting for an official reissue of This Earth! – exactly the same thing that is happening with the historically essential Just Music.

In Temporary Fault

20100203

PARCOURS BLEU A DEUX - Die Kainitische Stadt Über Abels Gebeinen (Recout)

Heinz Sauer (1932) ranks among the most prominent German saxophonists, a career including a number of significant collaborations with entities such as Albert Mangelsdorff, George Adams, Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland, Globe Unity Orchestra. In 1990 Alfred Harth had organized 2324 FU, a retrospective exhibition of his own visual art at Frankfurt’s Dominikanerkloster, a renowned gallery situated within a cloister. What he envisioned was a concert with Sauer to be held in the cloister’s Holy Ghost Church (devoted to Albert Ayler, one thinks…). This is exactly what happened, and Parcours Bleu A Deux were born.

As A23H puts it in a typically puzzling description, “the spirit and the reverb was the challenge”. PBAD were not meant to be a simple reed duet, but a completely autonomous small acousmatic unit; to achieve this goal, prerecorded tracks (also involving the voice of Isabel Franke reciting passages from the Apocalypse) and electronic emanations were added to the recipe. The musicians were able to maneuver those splinters via foot pedals while playing, the surprise factor guaranteed by the unforeseen manifestation of elements that might be perceived as not pertinent at first, appearing instead perfectly integrated in the music’s general unrest in a matter of seconds.

This CD (rough translation of the title: “The city of Cain built upon Abel’s bones”) comprises 70 minutes of extracts from performances dated 1991 and 1992 in Frankfurt, San Francisco and Vancouver. The initial set is introduced by a Canadian female host who translates the duo’s name as “Blue Horse Ride Of Two People” (indeed “Blue Course” means a lot of other things; surf the web, and rest assured that AH had thought of something different from what you’ll find). It becomes instantly clear that the improvisations are gifted with a remarkable structural definition deriving from the almost visible resolve of the performers, who literally ostracize bewilderment and chaos in favour of a logical kind of disquieting turbulence, remaining inside the enclosure of focused contamination. The timbral mixture is practically stainless, broad shoulders and stinging efficiency alternated to squealing and chirping with the same naturalness of an actor’s change of stage dress in relation to the upcoming scene.

The couple provides an indicator of how a clever improvisation should be carried on, boosting the tension level with hard staccatos, increasingly nervous quodlibets and sudden theatrical exploits highlighted by the appearance of the above mentioned prearranged fragments (my preference directed to the amorphous synthetic backgrounds that occasionally steer the sonic microcosm towards even more mysterious territories, still sweetening the brutality of certain dissonant counterpoints). Harth adds a personal dose of visceral physicality and grotesque drama by grunting, blathering and sardonically laughing into the instrument’s conduits, halfway through a good-humoured fiend and a vainglorious joker deriding the audience’s intellectual capacity. All in all, this is a difficult but – as always – extremely gratifying record that must be listened with concentration at full steam: the substance is thick, the artistry is indubitable, the technical proficiency proportional to the emotional intensity, only if you grant the music the due attention. Using this stuff as conversational backdrop means losing the coordinates of rationality, and perhaps some friend.

Harth and Sauer collaborated again - together with other instrumentalists - in 1995 in the ambit of FIM (Frankfurt Indeterminables Musiqwesen, the umpteenth collective formed by the protagonist of this series) for a tribute to fellow Frankfurter Paul Hindemith. The short life of PBAD is just another question mark in the chain of “whys” that characterizes this man’s creative being; for sure not many saxophone duets sound as lucid, provocative and ironically eccentric as this.

In Temporary Fault

20091001

TRIO TRABANT A ROMA – State Of Volgograd

Lindsay Cooper, Alfred 23 Harth and Phil Minton were members of the Oh Moscow venture, which – prior to this recording – had touched Volgograd during a Russian tour. In particular, Cooper and Harth were so bewildered - both by the visited cities and the divergence between those microcosms and the Western Culture (pun intended) – that, once returned, they were still feeling like “being in another state, a State Of Volgograd”. The triumvirate, formed by the Frankfurter in 1990 following an invitation by the Budapest Festival, owes its designation to the namesake cheap car manufactured in East Germany, which began to appear outside those borders subsequently to the Berlin Wall’s crumbling in 1989. To quote the originator, “… Trabant is also a word for a planet orbiting a star (…) Earth was under a new ‘orbital tent’ after the iron curtain came down. It was funny to see these odd eastern cars undertaking even long-distance trips through Europe - and, ultimately, all roads lead to Rome”.

Disgracefully, this small ensemble was short-lived; yet State Of Volgograd – the solitary official release – shines among the unconditional masterpieces of improvisational skill, a career landmark for everybody involved. Starting the 90s, Cooper’s multiple sclerosis was already taking a heavy toll, gradually making impossible for her to perform live; obviously, Oh Moscow dissolved, the last concert at 1993’s London Jazz Festival. Harth – as per Vladimir Tarasov’s words – became “as famous as Michael Jackson” in Russia’s avant-garde scene over lengthy periods of clandestinely smuggled records in “hidden narrow holes” before the Soviet Union’s collapse. A TV feature on him, Balance Action, was then realized by a local station. Indeed the relationship linking A23H with that part of the globe has always been pretty special (he went on to form QuasarQuartet, with Tarasov, in 1992).

But Trio Trabant A Roma stood apart from anything else. Three masters of the respective crafts in a setting that, quite impressively, leaves the individual silhouettes easily discernible while defining their union as one of the finest collectives carved in your reviewer’s memory. This recital, captured at Esslingen’s Dieselstrasse in 1991, testimonies about several truths. First, that Cooper, Harth and Minton are rare symbols of multiform instrumental enlightenment. Besides the habitual tools – yes, Minton’s voice is the quintessential human synthesizer – they shared piano duties; Cooper handles bassoon (listen to the marvellous phrasing in the initial minutes of “Orbital Tent”), electronic effects and sopranino, Harth tampers with various kinds of saxes, bass clarinet, melodica, sopranino, Farfisa organ and a Casio sampler. The record, in general, is informed by an intelligent use of technology, especially inventively warped sampling and discreet looping.

The tracks span across a number of moods and circumstances, nourishing an immediately identifiable temperament throughout. Minton sounds slightly more restrained than usual, alternating customary intrusions (the utter destruction of the melancholic tranquillity that opens “Et All Ways Budapest” is a gas indeed) to quasi-blues echoes and heartrending excursions halfway through pygmy chanting and mournful lamentation. To this day his duet with Harth in “Strasbourg Et Amor Trans’n’Dance” belongs in the top ten of my all-time favourite improvisations, suddenly turning into unachievable abstruseness replete with misshapen harmonic connections and excruciating grief, Cooper and 23 superimposing pitch-transposed, looped-and-modified lines over Minton’s drunken crooning in stunning fashion. The whole album is a glorification of total musicianship and an ode to reciprocal listening permeated by equal doses of joy, sorrow and childish astonishment, the musicians catching a glimpse of that “unknown something” which is usually obstinately ignored by the average instrumentalist, almost forgetting the qualities of technical development to run behind colourful butterflies of instant creation. The terzetto delivers in spades, creating music that – in absolutely spontaneous conceptions – is sweetly dissident, utterly immobilizing, restlessly strong, consistently pensive, and nonetheless so amusing.

That the material result this original to our ears 18 years from the taping is the revelation of a haunting permanence, a typical trait of significant art. Brief existence notwithstanding, Trio Trabant A Roma must be placed in a hypothetical Hall Of Fame of sonic originality. A combined vision that, now as then, guides the listener to a superior level of interaction with the unusual acoustic phenomena that only certain ambits of musical exploration can elicit.

20090811

More wonderment from the JUST MUSIC era

See also JUST MUSIC on ECM 1002 + selfproduction (1969)

and 4.Januar 1970 (selfproduction)

2009 is a fundamental moment in Alfred Harth’s life, in that he celebrates both the 60th birthday (on September 28th) and a 40-year career’s “jubilee”. We already talked about Just Music, one of the first improvisation ensembles recorded on ECM, whose activities were tragically under-documented to date. Luckily, Harth is retrieving additional material from the archives, these three records constituting as a good introduction as any to the collective’s stimulating methods. All of this great stuff is now available from the instigator himself through the Laubhuette imprint, and it comes without saying that you’d better start to be more aware of the roots of instrumental ad-libbing as opposed to having some “prophet of silence” dry your wallet with a hour of coughs, creaks and outside motorbikes surrounding two single “pings” and a “whirr”.

JUST MUSIC TRIOS (Laubhuette Productions)

Extraordinarily good-sounding, given that the recordings occurred in March 1970, the tracks contained by this disc - strangely enough - do not feature Harth but present a selection of improvisations by two dissimilar trios. In the first, Michael Sell (trumpet), Franz Volhard (bass) and Thomas Cremer (drums) show that brief disquisitions can yield excellent results. Sell is obviously a protagonist, his phrasing voluble without preponderance, a constant melodic resourcefulness at the basis of an invigorating cross of swiftness and concomitance in admirable interaction with the “fractured rhythm” section. If this piece has a defect, that should be its shortness. We’re soon rewarded by a superb “clean” set comprising again Volhard (this time on cello), Johannes Krämer (acoustic guitar) and Peter Stock (bass). This lengthier series is the ideal evidence of the sensitiveness-informed technical eminence of the musicians, who interact alternating exhilaration and open-mindedness during exchanges that range from sheer ebullience to classically-scented, chamber-like reflective interpretations of self-determination. Even within the same trio, the inherent subdivisions (practically, duos in three different combinations) reveal an “adult” approach to mutual give-and-take informed by a taste for first-rate tones which stamps this collection with a “not-to-be-missed” seal.

in Temporary Fault

and 4.Januar 1970 (selfproduction)

2009 is a fundamental moment in Alfred Harth’s life, in that he celebrates both the 60th birthday (on September 28th) and a 40-year career’s “jubilee”. We already talked about Just Music, one of the first improvisation ensembles recorded on ECM, whose activities were tragically under-documented to date. Luckily, Harth is retrieving additional material from the archives, these three records constituting as a good introduction as any to the collective’s stimulating methods. All of this great stuff is now available from the instigator himself through the Laubhuette imprint, and it comes without saying that you’d better start to be more aware of the roots of instrumental ad-libbing as opposed to having some “prophet of silence” dry your wallet with a hour of coughs, creaks and outside motorbikes surrounding two single “pings” and a “whirr”.

JUST MUSIC TRIOS (Laubhuette Productions)

Extraordinarily good-sounding, given that the recordings occurred in March 1970, the tracks contained by this disc - strangely enough - do not feature Harth but present a selection of improvisations by two dissimilar trios. In the first, Michael Sell (trumpet), Franz Volhard (bass) and Thomas Cremer (drums) show that brief disquisitions can yield excellent results. Sell is obviously a protagonist, his phrasing voluble without preponderance, a constant melodic resourcefulness at the basis of an invigorating cross of swiftness and concomitance in admirable interaction with the “fractured rhythm” section. If this piece has a defect, that should be its shortness. We’re soon rewarded by a superb “clean” set comprising again Volhard (this time on cello), Johannes Krämer (acoustic guitar) and Peter Stock (bass). This lengthier series is the ideal evidence of the sensitiveness-informed technical eminence of the musicians, who interact alternating exhilaration and open-mindedness during exchanges that range from sheer ebullience to classically-scented, chamber-like reflective interpretations of self-determination. Even within the same trio, the inherent subdivisions (practically, duos in three different combinations) reveal an “adult” approach to mutual give-and-take informed by a taste for first-rate tones which stamps this collection with a “not-to-be-missed” seal.

in Temporary Fault

JUST MUSIC GROUPS & DUOS (Laubhuette Productions)

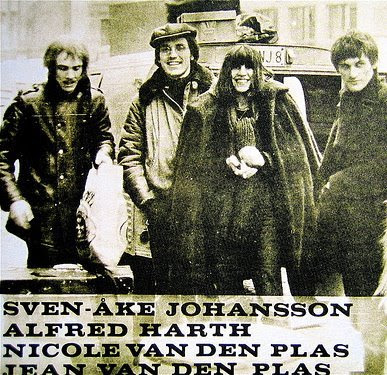

Just listening to the radiophonic excerpt which opens the CD, recorded at Hessischer Rundfunk in 1968 and featuring snippets of interview (in German) with a 18-year old Harth - who sounds like a well-trained host in answering the real host’s questions - is enough to make one instantly curious. Yet it is once again the incredible maturity of the music presented, intelligently sequenced in the subsequent tracks, which must be taken into account to establish the absolute importance of these archival materials. These pieces – fantastic how the typical background hum contributes to the fascination during the playback – appear as a cross-pollination of atonal thematic jazz and instant-reaction heterodoxy - without excess of transcendental euphoria - in perennial recusant enlightenment. The chief initiator, on tenor sax, is flanked by Dieter Herrman on trombone, besides the usual suspects Krämer (guitar), Volhard (cello), Stock (bass) and Cremer, here puzzlingly credited with “inflating drums” (STOP PRESS: the just-received explanation reads "Cremer inflated his snare and toms with the help of a hose by blowing air with his mouth that changed the pitch of the drums while beating them"). While the dialogues between the not-yet-Mr.23 with, respectively, Cremer and Herrman describe a sharp journeying around the possibilities of two-part counterpoint without devastating apogees or reprehensible utilizations of formulas, the cream lies within three marvellous expressions by the Harth/Nicole Van Den Plas duo, correspondingly titled “Call & Suspense”, “Durus” and “Reverserenity”, the latter characterized, as per the title’s hint, by sonorities based on reverse-tape techniques utilized with extreme soberness. The saxophonist - who in this case plays bass clarinet, violin, harmonica and other objects - and his (at that time) life partner, also vocalizing in semi-ritual fashion, share a noticeable confident comprehension, demonstrating a deeper degree of intuitive intimacy which is usually the crucial factor for intense revelations in improvisational ambits. The disc is concluded by a trait-d’union recording – “near the end of Just Music & ahead of the group E.M.T.” in A23H’s words – of the quartet formed by Harth, Van Den Plas, her brother Jean Van Den Plas (bass) and Paul Lovens (drums), which in a way symbolizes the transformation of ideals and, especially, the ever-shifting intellectual qualities of a man whose artistic aims were probably too high in relation to a proverbial modesty, as hundreds of imitators found a quick ascent to fame and fortune given their exactly opposite attitude (“let’s steal, then we’ll see”). But time, someone says, is a gentleman, and properly schooled ears are going to do the rest for a complete recognition of “who came first”.

in Temporary Fault

JUST MUSIC ENSEMBLES (Laubhuette Productions)

A few additional soldiers join the squad. Harth and friends are flanked in a couple of instances by other free-thinkers, responding to the names of Witold Teplitz (clarinet), Hans Schwindt (alto sax), Thomas Stoewsand (cello) and Andre De Tiege (viola). Ensembles is probably the record in which the ratio between the modernity of the overall sound and the old age of the tapes is in every respect astonishing. A set like the one recorded on September 13, 1968 at the Liederhalle, Mozartsaal in Stuttgart could easily have been composed (on the spot, naturally!) and released today without almost anyone noticing that 1) the players are out-and-out teenagers and 2) the music comes from the post-Palaeozoic era of collective perspicuity, Harth allegedly unaware of entities such as AMM or SME which were evidently navigating contiguous seas. What we need to stress yet again is the impressive up-building of the interplay, which often start from veritable compositional illuminations in turn giving life to earnestness-driven hypotheses for a new contrapuntal design, without the necessity of recurring to tricks or, even worse, reducing the whole to unwarranted noise. In reality, what immediately strikes the ears is the non-difficult digestibility of this material: despite the lack of a commonly intended “theme” or some “melody” to be caught from, and the fact that nonconformity can be detected nearly everywhere, that classic sense of fulfilment deriving from the fine-tuning of dissonance resolving in catharsis permeates the air every time we stop and concentrate a tad more on the wholesome allure of these sounds. The conclusive two parts of “Radio Live Concert In Prague” might be considered among of the most evocative moments this reviewer has experienced in hundreds of hours of A23H-typified expressions, an exquisite meshing of controlled apprehension and cultivated aggrandisement of minuscule mechanisms, sustaining the weight of a prolonged duration to reveal a world of correspondences and interrelationships one would gladly like to acknowledge as “ideal”. An inspiring ending for this marvellous triptych, chock full of secluded beauties finally revealed to worthy audiences. If many people had conveniently “forgotten” to attribute the deserved place in the history of contemporary improvisation to Alfred Harth’s conceptions and ideas, now blind shades and earplugs must be thrown away once and for all. This music should be studied.

in Temporary Fault

in Wikipedia

20090510

E.M.T. (Laubhuette Productions)

This instalment of the “Memories” is particularly important, despite the fact that E.M.T. belong to a very early period of Alfred Harth’s artistic life and, as such, reveal a lot of the initial “work-in-progress” phase of a career which touched on a multitude of different aspects. This notion is strictly linked to the other fundamental root of another cooperative improvising medium founded by the same person - Just Music, to which we will return in an upcoming chapter.

The origin of the E.M.T. collective dates from 1972, year in which AH decided to use three letters to designate a project destined, in his vision, to remain unlinked from any idea relative to a repertoire or a style, and whose meaning was left open to interpretation. The saxophonist recalls that, asked about the name, the favourite translations were “Energy/Movement/Totale”, “Extreme Music Troop” and “European Music Tradition”, the latter a bizarre choice since this stuff has very little “traditional” accents, unless you want to consider free jazz as folklore. It is interesting to note that the Frankfurter was completely unaware of AMM and SME in that period, therefore copycat-ism is out of the question: what was coming from these people was entirely original, like it or not.

The basic nucleus of E.M.T. consisted of Harth on reeds and assorted sonic tools, his then spouse Nicole Van Den Plas on piano and electric organ, brother Jean Van Den Plas on cello and bass and the percussionist who, in AH’s words, plays like “rolling ocean waves”, Sven-Åke Johansson (who, in turn, called it “dynamic vibrations”). Additional contributors (on the recorded material checked for this article) included Helmuth Neumann and Michael Sell, both on trumpet and Liliane Vertessen on trombone.

Harth had begun a steady live activity with Van Den Plas in Belgium a couple of years prior, playing with Peter Kowald and Paul Lovens among others. Johansson, who had performed first with him in 1968, joined them for a trio immortalized in the only official release, 1974’s Canadian Cup Of Coffee on SAJ. The three were intrigued by visual arts, and the drummer also recognized the influence of Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (although his version of Sprechstimme is more similar to a drunk man mumbling amid trash cans in an alley…). The tracks’ names were so-called “fanciful inventions” by our main character, who wanted to mix exotic hints, European classicism and German Dada in the same cauldron.

The above mentioned record is probably the most restrained (!) example of what E.M.T. were able to do, as the sense of humour characterizing several of its sections is pronounced and typically vivid. Still, when one lends ears to the recordings dating from 1973 - gathered in two CDRs respectively named Haus Dornbusch / Heidnische Klänge / Heilbronn and Hamburg Fabrik - acknowledging the expressive urgency and lawless vehemence of the ensemble comes rather natural. E.M.T. treated the need of telling the truth against refined insignificance like an affair of honour, pushing their instruments to the limit almost everywhere yet managing to find some available space for duets or, if so preferred, parallel solos that demonstrate pragmatism and perseverance even in absence of aesthetical beauty. Face it: these incensed collections run well over 70 minutes, and attempting a moment-by-moment description would be pathetic. This is about the portrayal of a spirit, not visualizing instrumental colours. Of course, Van Den Plas is as far from grandiloquent as possible, her role apparently tailored to connect the extrovert passions of Harth and Johansson, the whole often turning into veritable frenzies informed by forward-looking wholeheartedness. But all the participants, in every circumstance, seem to listen to no reason, merely worried with keeping the embitterment against the potential enemy active. Let’s not forget the politically charged era in which this was happening: accepting those seemingly incessant blowouts will then be painless - maybe. Let me stress it: a relaxing experience this ain’t, finding correlations also easier said than done. E.M.T. obeyed to a hard-nosed conviction of creative paganism, and there was no time for rethinking. If you still want to do business with this concept three decades and a half later prepare to shed your ear fluff, as this music refuses the definition of “embellishment”.

Considering that the travelling for that era’s tours was made, according to the reports, utilizing vehicles in the category of Renault 4, Citroen 2CV and Volkswagen Beetle, one justifies the musicians’ urge of stretching someone else’s nerves once they went on stage after those uneasy trips.

E.M.T. in Wikipedia

in Temporary Fault

20090223

CASSIBER

Man Or Monkey

Man Or Monkey  The Beauty And The Beast

The Beauty And The BeastIn a perfect world (pun intended), the finest music would result in a composition that sounds like an impromptu outburst of accomplished creativity – no pre-established rules, no rigidness, no nothing as Peter Brötzmann would have it. Cassiber (originally Kassiber, the name deriving from the Slavonic term indicating a “message smuggled out of prison”) were maybe the group that got nearest to that vision. The band’s official trace starts from 1982, but Christoph Anders, Chris Cutler, Heiner Goebbels and Alfred Harth had already met five years earlier, at the times of the Sogennantes Linksradikales Blasorchester. Interested by punk, willing to mix that influence with radical jazz, classical and various kinds of interference – made concrete by the use of radio and TV snippets and all sorts of samples – the original quartet recorded a couple of gems between 1982 and 1984, their significance at a stage of intensity and unrefined magnificence equivalent to the most essential politically committed talents of that (and any) era. After Harth’s departure in 1984 to form Gestalt et Jive and Vladimir Estragon, the remaining three kept producing great work in albums such as Perfect Worlds (there you go) and A Face We All Know, both on Recommended. Yet this writer has always perceived Cassiber minus A23H as a healthy body missing a limb.

Still, what really identifies the quintessence of this coherently wild corporation is probably Anders’ perennially hollered delivery: an exaggerated, histrionic mixture of irony, rage and sorrow that constitutes a veritable trademark instantly evident in “Not Me”, Man Or Monkey’s icebreaker. This introduction is unquestionably ill-mannered, an instantly nervous concoction of non-existent harmonic contexts where the collective multi-instrumentalist ability of the quartet is straight-away detectable, the sound shifting across many finalities without a definite answer to the needs elicited by this suspension. The repeated piano note constituting the backbone of “Red Shadow” brings to mind the first movement of Fred Frith’s “Sadness, Its Bones Bleached Behind Us” on The Technology Of Tears, whereas the fake Mariachi style of the impressively anguishing “Our Colourful Culture” is incontestably the most dramatic moment of the album, Anders reciting Cutler’s lyrics portraying a desperate man rambling about his people starving and getting killed while “we fight in the mountains”, the song ending with the protagonist’s spine-chilling hysterical laughter as the main theme fades to black. Curiously, this is the only segment in which the drumming chores are handled by another musician, Peter Prochir. “O Cure Me” sees the fervent vocalist declaiming a passage by Johann Sebastian Bach along delirious instrumental circumstances where contrapuntal implicitness and transitory phases are the menu du jour, the whole underlined by a cheap sequencer-based progression. Perhaps this release is where the doses of anarchy are more abundant than anywhere else, as clearly demonstrated by the free-for-all character of the lengthy title track and the Miles Davis-meets-dilettante guitarist adventure of “Django Vergibt”. The best was yet to come, though.